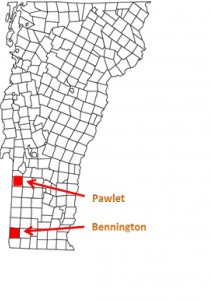

Working for the Center, every once in a while I get a chance to go off to a far flung place to poke my head into catch basins and outlet pipes. Last month I traveled to southwestern Vermont to meet up with a team of folks to track down illicit sewage discharges. Over the course of several years, Vermont’s Department of Environmental Conservation (VTDEC) has been systematically supporting illicit discharge investigations in different parts of the state with the overall aim of reducing  bacteria levels in its waterways. This year, VTDEC’s focus has been on the town of Bennington and the small village of Pawlet. Lucky for me, I had an opportunity to help out with the effort.

bacteria levels in its waterways. This year, VTDEC’s focus has been on the town of Bennington and the small village of Pawlet. Lucky for me, I had an opportunity to help out with the effort.

For one week I joined a motley crew: our Fearless Leader (ace illicit discharge detective Dana Allen from Watershed Consulting Associates), our Local Liaison (Hilary Solomon with Poultney Mettowee Natural Resources Conservation District), our Watershed Statesman (Jim Pease from Vermont DEC), our Talented Trainers (Karen and Scott Reynolds with Environmental Canine Services), and their two Sewage Sniffers (dogs, Logan and Sable). We were too busy looking for the next catch basin to notice how many funny looks we got as we traveled around the streets as a pack. I’m sure we got a few!

Approximately six years ago, Karen and Scott took it upon themselves to start training dogs to identify the smell of human sewage to assist with IDDE efforts. Once trained, the canines can take a sniff of a catch basin or an outfall and identify within seconds if human wastewater is (or recently was) present, even at very low concentrations. On the other hand, it takes minutes for us humans to arrive at the same conclusion using field and lab equipment – IF there is even enough flow available to take a sample. Each dog has adopted a different way to alert his human handlers that he has found a positive hit for sewage: Logan sits down, and Sable barks. Their noses have different levels of sensitivity, so when the canines work as a team, they can even provide some perspective on where sewage presence is mild and where it is strong.

A great deal of leg-work happened prior to our one-week investigation. In Pawlet, which has been experiencing high e. coli levels in a section of Flower Brook that passes through the center of the village, Hilary Solomon had spent the summer going door-to-door to find details on the types and ages of septic systems servicing each property. This effort would potentially provide some insight into whether failing septics are contributing to the e. coli problem in a particular location. Concurrently, Watershed Consulting Associates had inspected outfall pipes coming into Flower Brook, looking for any dry weather flow or signs of past illicit discharges. When there was enough flow present, they ran tests for e. coli, pH, conductivity, ammonia, potassium, detergents, and chlorine. The same tests were done at outfalls throughout Bennington. With these results in hand, a picture started to form. We were able to focus our attention on certain pipes and stream sections in each locality where we could bring the dogs for the ultimate sniff test.

After three days of the canine team sniffing streams, springs, outfalls, catch basins, and manholes, our crew identified at least three highly likely sources of wastewater pollution. Although further smoke/dye/video testing should help confirm these, preliminary findings include: an underground spring flow that may be intermingling with a residential septic system and leaching sewage into the stream; a roof drain that may be funneling septic field leachate into a road-side ditch; and a sanitary sewer leaking into a storm drain pipe where they are in close proximity to each other under a street. We can only hope that resolving these leaks and cross-connections are relatively simple. Only further investigation will tell.

The dog’s method is not completely protected from outside interference (such as smells from nearby sewage vent stacks). But having seen in person how the canine team works, I have to say that their method is quite revolutionary for IDDE field work which is often clunky and slow going. Not only did they speed up our investigation, but the dogs’ keen sense of smell may have led us to track down sources that we and our equipment may have otherwise missed.

Stormwater and Watershed Planner

Laurel Williamson is a Stormwater and Watershed Planner at the Center for Watershed Protection. She is located out of the Charlottesville, VA satellite office where she works on watershed field assessments, stormwater management trainings, and technical assistance to local and state governments. In the past, she has worked for the County of Albemarle, VA on stormwater BMP maintenance inspections and at the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay, coordinating the citizen water quality monitoring program. Laurel has a B.A. in Environmental Science and a B.A. in Environmental Thought & Practice from the University of Virginia.